Click Here Back to SAS Stories

If you would to like to comment on this story or add something, maybe you were there, please do so on csqn@hotmail.com

Who Dares Wins

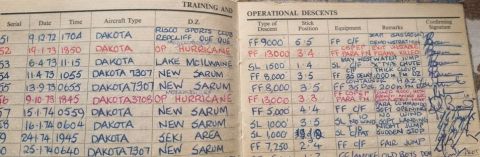

Below is the parachute log book entry for the operation

described below

described below

PARACHUTE OPERATIONS IN THE RHODESIAN SPECIAL AIR SERVICE

After passing the Rhodesian SAS selection course in Inyanga I joined the Rhodesian Army. I signed the ‘dotted line’ on the day before my 18th birthday on 4 September 1970.

After 6 months of specialised SAS training my basic parachute course had me jumping out of post WWII Dakota’s (C47) using the white WWII ‘X’ type parachutes. Thereafter static line parachuting was done using the T10 American type and later the South African Saviac parachute.

I was presented with Rhodesian SAS wings on 13 March 1971.

Shaking hands with Group Captain Graham Smith OBE, ICD, ED, MID. Take note : Parachute wings not yet sewn onto Green’s jacket.

Age : 18 years 6 months and 8 days. 9 parachute jumps under my belt and ready to go on ops

ADVANCING TO HALO PARACHUTING

During November 1972 I was selected to attend the 4th SAS HALO free-fall course from 20 July – 24 August 1972 at No 1 Parachute Training School based at New Sarum which was the Rhodesian Air Force base on the outskirts of Salisbury.

Four members were selected and three passed these being Lt Chris Schulenburg, Lt Ron Marillier and myself, then a Lance Corporal .

Four members were selected and three passed these being Lt Chris Schulenburg, Lt Ron Marillier and myself, then a Lance Corporal .

OPERATION HURRICANE

Herewith my story of the first operational night free-fall, by the SAS into enemy territory.

It was a Friday on the 19th January 1973 when eight free fallers were summoned to attend an urgent briefing at 2 Brigade Headquarters in Cranborne Barracks, Salisbury.

The situation was that a prominent Rhodesian citizen (Gerald Hawksworth) had been abducted by a communist terrorist group, and was being forcibly ‘frog marched’ out of Rhodesia into Mozambique and then onto a Rhodesian terrorist base situated inside Zambia.

Intelligence revealed that the route and our mission was to do a night free-fall parachute jump into Mozambique, find a suitable parachute DZ (Dropping Zone), guide SAS parachute troops within a Dakota aircraft over the DZ, and thereafter lay ambushes so as to cut off this terrorist group and to rescue the abductee.

The group of eight SAS soldiers were split into two teams of four. Equipment, rations and weapons were drawn and we were driven out to New Sarum for some last minute parachute training prior to the parachute deployment.

We were not as nervous as anticipated, and this was perhaps due to everything being rushed. There was much excitement in the air.

Part of free fall parachute training entails practising simulated flight, and whilst each of us were strapped into a harness, and raised some 10 feet above the ground. Once assuming the body flight position, various techniques were practiced. The parachute instructors would comment on body position and rectify any position which was not right.

Our group of four consisted of Lt Chris Schulenburg, Sgt Frank Wilmot, Cpl Danny Smith and myself. I was a L/Cpl at the time and was a young 20 year old.

Whilst conducting rather hasty free-fall training, our body positions were being analysed to ensure we would fall stable prior to pulling our ripcords. The three of us were fine, however one of the PJI’s (Parachute jumping instructors) was not happy with the flight position of Sgt Frank Wilmot. His arms did not appear to be symmetrical during the simulation test, and it was pointed out to him that he should concentrate on this, because should it not be correct, he would go into a right hand spin. This comment bothered me, and I made a mental note of it.

It was getting late in the afternoon, we had completed our training and had made all necessary adjustments to our webbing along with the heavy back packs we would parachute in with.

The Army padre (Padre Norman Woods was his name) appeared, as did our Rhodesian Army commander (Lt General Peter Walls). It was comforting to have our General come and wish us luck, but the Army padre wasn’t as comforting, especially when he handed each of us a small pocket bible – did he know anything we didn’t?

It was now late afternoon and it was time to go and board the Dakota.

The SAS Commanding Officer, Major Brian Robinson came along to ensure that all went well. He wanted to be with his men all the way.

There were two free fall teams, each team consisting of 4 members. Our team callsign being Pappa 1 (P1) whilst the other being Pappa 2 (P2). The team leader of P2 was Capt Garth Barrett.

The flight out of Rhodesia and into Mocambique was uneventful and seemed to take forever. Paratroopers about to embark on something like this are not averse to telling jokes or creating small talk. It doesn’t get rid of the nerves and in my opinion, just accentuates such as it reveals rather than conceals.

It was becoming dark but we had a good moon, we sat quietly with the only sounds being the constant loud drone of the Dakota’s Pratt & Whitney engines.

It was nearing quarter to seven at night when we were ordered to stand up, check equipment and move towards the door. It was difficult and uncomfortable to walk to the open aircraft door. Our back packs were fully laden, our webbing was full of ammunition, water and emergency rations and our folding butt FN rifles were securely wrapped to the left hand side of our bodies. Our free fall parachute webbing was also tightly fitted.

We were flying at an altitude of 13,000ft AGL (above ground level) so as to not alert those living on earth below of our presence over their territory. It would also be too dangerous to fly higher without personal oxygen masks, as normal oxygen levels would be non-existent. As it was, oxygen levels start to deplete at 8,000ft above above ground level (AGL). We were 5,000 ft above that level.

I was number three in the ‘stick’ and it was only Sgt Frank Wilmot who would follow me out. The light over the door turned from red to green which gave the signal to exit. The fumes of the Dakota engines made me catch my breath as I exited the aircraft, plummeting to earth at a great speed.

One normally ‘pulls the ripcord’ to deploy the main parachute at 2,500 ft AGL and one allows for about 500ft for the parachute to fully deploy. This allows for +- 2,000ft to get one’s bearings, lower one’s back-pack on a 30ft rope, select a suitable open landing area, aim for it, keeping eye on the others and hopefully to land safely.

Although dark, the moon provided enough light to keep the horizon visual, thus assisting us to be able to free-fall in a stable condition. I could see the other two below me and knew that Sgt Frank Wilmot would be above me.

At about 10,000 ft I was most alarmed to see Frank suddenly overtake me in a rather dangerous right hand spin. The spin worsened and I immediately thought about what the PJI had said earlier on in the afternoon. If Frank did not counter the spin, it would become faster and he would not be able to (due to the extreme centrifugal force) draw his right arm in to pull the ripcord.

Whilst keeping an eye on Frank, which was difficult due to the light, I pulled my ripcord, saw Frank continue to plummet and after my parachute opened I lost sight of him.

I knew that he hadn’t been able to pull his ripcord and if his emergency parachute had not opened, he would be dead.

Through the glint on the green parachutes from the moon above, I could see that Lt Schulenburg and Cpl Smith’s parachutes had opened.

We all landed safely, grouped and established communications with the Dakota to let them know that Sgt Wilmot had had a complete parachute malfunction and had fallen to his death.

The plan was to locate a DZ for SAS paratroopers who were due to come in later that night.

It is not easy to find a man in the dark, especially in a wooded area. There is not too much light to aid one and when one considers the distance we walked coupled to the amount of drift once a parachute opens versus a paratrooper whose parachute hasn’t opened can be some distance to search.

I was the first to find Sgt Wilmot. What actually happened was that his main parachute had not deployed, neither had his reserve parachute (despite having being fitted with an emergency opening device – known as a Sentinal).

He had gone through a tree, which had ripped off his helmet, and had hit a large boulder resulting in a massive head injury. It was a horrid and awful experience to see this.

The back part of his parachute had burst open, but the actual parachute remained in its deployment sleeve. I pulled the parachute out of its sleeve and wrapped his body in it. His reserve parachute had also not deployed meaning that the automatic Sentinal device had also completely malfunctioned.

It was surreal to pick up Sgt Wilmot as I had never lifted a dead body before. I could feel that he must have broken every bone in his body.

His back pack had also burst open, with tins of food lying splattered around. It was the glint of the moon on the tins that caught my eye whilst looking for him. Had it not been for that, I believe we would only have found him the next day.

We had to continue with our mission, and that was to locate a suitable dropping zone for the static line parachute deployment of SAS troops at midnight.

We left Sgt Wilmot more or less we had found him, and set off.

Shortly before midnight, we realized that there was no suitable DZ to be found, got onto the radio, made contact and advised the SAS headquarters of the present situation. Our task was to then go back and find Sgt Wilmot’s body, and to then expect a helicopter pick up at first light.

Walking back on a worked-out compass back-bearing led us back to the exact spot where we had left Sgt Wilmot. I believe that this map reading skill by Lt Schulenburg was remarkable, especially being that it was at night (by now the moon had disappeared), we had no sleep or rest and the bush was relatively dense.

At first light, a helicopter was guided onto our position. This was also a brave effort by the pilot as he had to fly in alone. Due to the distance he had to fly, the accompanying flight technician had to be left behind to have more fuel and less weight to achieve the flying distances required.

I felt alone when the helicopter took off for Rhodesia with poor old Frank along with the parachutes on board.

Any terrorist group/s in the area would now know that Rhodesian forces were in the area. We therefore took it on that our presence had been compromised.

We were quite deep into Mozambique, it was weird. Everything was so quiet and as a three-man team we had to move on. The terrain would change from mopani forest to thick everglade bush. It was very humid and being the rainy season, there were occasional thunderstorms accompanied by long stretches of heavy rain. When the sun came out, it made it even more humid. Mosquitos at night harassed us and there was no respite.

During radio schedules we were informed where the other pathfinder team (P2) was, and that there had been a successful static line drop of SAS troops. I thought they were fortunate as there is safety in numbers. What if we were ambushed- we would surely be outnumbered, and we wouldn’t have enough fire power to counter the attack.

It took us about a week until we met up with the other group. It was a great feeling to be with them all, and the first conversation revolved around the demise of Sergeant Frank Wilmot.

The whole group was split up into various groups so as to send out patrols to find the terrorist group with Hawksworth. Tracks were picked up and ambushes laid. Nothing came of all the effort. They had got away.

This was the very first night free fall operation into enemy territory by the SAS. It made history and it is believed to have been a world’s first. I was proud to have been amongst the first who did it but also extremely saddened that we had lost a very fine soldier in the process.

We were now totally aware of what it was like to operate in enemy territory, and many more operations continued in Mozambique. We found and destroyed terrorist camps, had many contacts with the enemy and a new style of SAS operations was starting to emerge.

As time moves on, a few minutes is put aside around 18h40 on the 19th January of each year and a small tot of whisky, coupled to a phone call to Chris Schulenburg is conducted in memory and respect for Sergeant Frank Wilmot. And at some point during the 19th of January of each year that goes by, I make a point in contacting Brian Robinson of the occasion. Brian remembers the occasion all too well, as this tragic accident happened on his birthday.

The situation was that a prominent Rhodesian citizen (Gerald Hawksworth) had been abducted by a communist terrorist group, and was being forcibly ‘frog marched’ out of Rhodesia into Mozambique and then onto a Rhodesian terrorist base situated inside Zambia.

Intelligence revealed that the route and our mission was to do a night free-fall parachute jump into Mozambique, find a suitable parachute DZ (Dropping Zone), guide SAS parachute troops within a Dakota aircraft over the DZ, and thereafter lay ambushes so as to cut off this terrorist group and to rescue the abductee.

The group of eight SAS soldiers were split into two teams of four. Equipment, rations and weapons were drawn and we were driven out to New Sarum for some last minute parachute training prior to the parachute deployment.

We were not as nervous as anticipated, and this was perhaps due to everything being rushed. There was much excitement in the air.

Part of free fall parachute training entails practising simulated flight, and whilst each of us were strapped into a harness, and raised some 10 feet above the ground. Once assuming the body flight position, various techniques were practiced. The parachute instructors would comment on body position and rectify any position which was not right.

Our group of four consisted of Lt Chris Schulenburg, Sgt Frank Wilmot, Cpl Danny Smith and myself. I was a L/Cpl at the time and was a young 20 year old.

Whilst conducting rather hasty free-fall training, our body positions were being analysed to ensure we would fall stable prior to pulling our ripcords. The three of us were fine, however one of the PJI’s (Parachute jumping instructors) was not happy with the flight position of Sgt Frank Wilmot. His arms did not appear to be symmetrical during the simulation test, and it was pointed out to him that he should concentrate on this, because should it not be correct, he would go into a right hand spin. This comment bothered me, and I made a mental note of it.

It was getting late in the afternoon, we had completed our training and had made all necessary adjustments to our webbing along with the heavy back packs we would parachute in with.

The Army padre (Padre Norman Woods was his name) appeared, as did our Rhodesian Army commander (Lt General Peter Walls). It was comforting to have our General come and wish us luck, but the Army padre wasn’t as comforting, especially when he handed each of us a small pocket bible – did he know anything we didn’t?

It was now late afternoon and it was time to go and board the Dakota.

The SAS Commanding Officer, Major Brian Robinson came along to ensure that all went well. He wanted to be with his men all the way.

There were two free fall teams, each team consisting of 4 members. Our team callsign being Pappa 1 (P1) whilst the other being Pappa 2 (P2). The team leader of P2 was Capt Garth Barrett.

The flight out of Rhodesia and into Mocambique was uneventful and seemed to take forever. Paratroopers about to embark on something like this are not averse to telling jokes or creating small talk. It doesn’t get rid of the nerves and in my opinion, just accentuates such as it reveals rather than conceals.

It was becoming dark but we had a good moon, we sat quietly with the only sounds being the constant loud drone of the Dakota’s Pratt & Whitney engines.

It was nearing quarter to seven at night when we were ordered to stand up, check equipment and move towards the door. It was difficult and uncomfortable to walk to the open aircraft door. Our back packs were fully laden, our webbing was full of ammunition, water and emergency rations and our folding butt FN rifles were securely wrapped to the left hand side of our bodies. Our free fall parachute webbing was also tightly fitted.

We were flying at an altitude of 13,000ft AGL (above ground level) so as to not alert those living on earth below of our presence over their territory. It would also be too dangerous to fly higher without personal oxygen masks, as normal oxygen levels would be non-existent. As it was, oxygen levels start to deplete at 8,000ft above above ground level (AGL). We were 5,000 ft above that level.

I was number three in the ‘stick’ and it was only Sgt Frank Wilmot who would follow me out. The light over the door turned from red to green which gave the signal to exit. The fumes of the Dakota engines made me catch my breath as I exited the aircraft, plummeting to earth at a great speed.

One normally ‘pulls the ripcord’ to deploy the main parachute at 2,500 ft AGL and one allows for about 500ft for the parachute to fully deploy. This allows for +- 2,000ft to get one’s bearings, lower one’s back-pack on a 30ft rope, select a suitable open landing area, aim for it, keeping eye on the others and hopefully to land safely.

Although dark, the moon provided enough light to keep the horizon visual, thus assisting us to be able to free-fall in a stable condition. I could see the other two below me and knew that Sgt Frank Wilmot would be above me.

At about 10,000 ft I was most alarmed to see Frank suddenly overtake me in a rather dangerous right hand spin. The spin worsened and I immediately thought about what the PJI had said earlier on in the afternoon. If Frank did not counter the spin, it would become faster and he would not be able to (due to the extreme centrifugal force) draw his right arm in to pull the ripcord.

Whilst keeping an eye on Frank, which was difficult due to the light, I pulled my ripcord, saw Frank continue to plummet and after my parachute opened I lost sight of him.

I knew that he hadn’t been able to pull his ripcord and if his emergency parachute had not opened, he would be dead.

Through the glint on the green parachutes from the moon above, I could see that Lt Schulenburg and Cpl Smith’s parachutes had opened.

We all landed safely, grouped and established communications with the Dakota to let them know that Sgt Wilmot had had a complete parachute malfunction and had fallen to his death.

The plan was to locate a DZ for SAS paratroopers who were due to come in later that night.

It is not easy to find a man in the dark, especially in a wooded area. There is not too much light to aid one and when one considers the distance we walked coupled to the amount of drift once a parachute opens versus a paratrooper whose parachute hasn’t opened can be some distance to search.

I was the first to find Sgt Wilmot. What actually happened was that his main parachute had not deployed, neither had his reserve parachute (despite having being fitted with an emergency opening device – known as a Sentinal).

He had gone through a tree, which had ripped off his helmet, and had hit a large boulder resulting in a massive head injury. It was a horrid and awful experience to see this.

The back part of his parachute had burst open, but the actual parachute remained in its deployment sleeve. I pulled the parachute out of its sleeve and wrapped his body in it. His reserve parachute had also not deployed meaning that the automatic Sentinal device had also completely malfunctioned.

It was surreal to pick up Sgt Wilmot as I had never lifted a dead body before. I could feel that he must have broken every bone in his body.

His back pack had also burst open, with tins of food lying splattered around. It was the glint of the moon on the tins that caught my eye whilst looking for him. Had it not been for that, I believe we would only have found him the next day.

We had to continue with our mission, and that was to locate a suitable dropping zone for the static line parachute deployment of SAS troops at midnight.

We left Sgt Wilmot more or less we had found him, and set off.

Shortly before midnight, we realized that there was no suitable DZ to be found, got onto the radio, made contact and advised the SAS headquarters of the present situation. Our task was to then go back and find Sgt Wilmot’s body, and to then expect a helicopter pick up at first light.

Walking back on a worked-out compass back-bearing led us back to the exact spot where we had left Sgt Wilmot. I believe that this map reading skill by Lt Schulenburg was remarkable, especially being that it was at night (by now the moon had disappeared), we had no sleep or rest and the bush was relatively dense.

At first light, a helicopter was guided onto our position. This was also a brave effort by the pilot as he had to fly in alone. Due to the distance he had to fly, the accompanying flight technician had to be left behind to have more fuel and less weight to achieve the flying distances required.

I felt alone when the helicopter took off for Rhodesia with poor old Frank along with the parachutes on board.

Any terrorist group/s in the area would now know that Rhodesian forces were in the area. We therefore took it on that our presence had been compromised.

We were quite deep into Mozambique, it was weird. Everything was so quiet and as a three-man team we had to move on. The terrain would change from mopani forest to thick everglade bush. It was very humid and being the rainy season, there were occasional thunderstorms accompanied by long stretches of heavy rain. When the sun came out, it made it even more humid. Mosquitos at night harassed us and there was no respite.

During radio schedules we were informed where the other pathfinder team (P2) was, and that there had been a successful static line drop of SAS troops. I thought they were fortunate as there is safety in numbers. What if we were ambushed- we would surely be outnumbered, and we wouldn’t have enough fire power to counter the attack.

It took us about a week until we met up with the other group. It was a great feeling to be with them all, and the first conversation revolved around the demise of Sergeant Frank Wilmot.

The whole group was split up into various groups so as to send out patrols to find the terrorist group with Hawksworth. Tracks were picked up and ambushes laid. Nothing came of all the effort. They had got away.

This was the very first night free fall operation into enemy territory by the SAS. It made history and it is believed to have been a world’s first. I was proud to have been amongst the first who did it but also extremely saddened that we had lost a very fine soldier in the process.

We were now totally aware of what it was like to operate in enemy territory, and many more operations continued in Mozambique. We found and destroyed terrorist camps, had many contacts with the enemy and a new style of SAS operations was starting to emerge.

As time moves on, a few minutes is put aside around 18h40 on the 19th January of each year and a small tot of whisky, coupled to a phone call to Chris Schulenburg is conducted in memory and respect for Sergeant Frank Wilmot. And at some point during the 19th of January of each year that goes by, I make a point in contacting Brian Robinson of the occasion. Brian remembers the occasion all too well, as this tragic accident happened on his birthday.

Back to the top

_________________

Who Dares Wins